Mankind is blessed with the wonderful trait of creativity and progressive thinking. These qualities have allowed us to collectively advance ourselves through the conceptualization and combination of revolutionary ideas. Starting from the seemingly instinctive discovery of eating more than one food source at a time—thus creating the old protein, staple and fibre combo—fusing and combining things on the plate has played a significant role in humanity’s culinary evolution.

Fortunately we’re not going to dissect what made the carnivorous Neanderthals decide to cook vegetables back in the day, but we are going to look at the upbringing of modern fusion cuisine, how it has become popular and why some may have a love-hate relationship with it.

This chic movement is often credited to Wolfgang Puck and his delightful, timeless creations such as the buffalo chicken spring roll and BBQ nachos, but to call the fusion food movement something new would be rewriting history. “Fusion food”, the blending of culinary worlds to create new, hybrid dishes, has been around since the beginning of trade; so vast is its history that it is almost impossible to discern the original iteration of fusion food. The most famous example, however, so ubiquitous that it is difficult to connect origin to culture, is the noodle: spaghetti would not exist if the Chinese had not perfected the method first.

Blending two or more culinary traditions from different areas to create innovative and often very interesting dishes, the idea of fusion cuisine has since gained popularity worldwide, especially over the last decade. It tends to be more common in culturally diverse and metropolitan areas, where there is a wider audience for such food. Some common examples include Thai-Vietnamese’s Pacific Rim cuisine and Tex-Mex food.

While we’ve established that the roots of fusion cuisine are probably ancient (since humans have spread out enough to exchange culinary heritage for centuries), the concept became popularized in the 1970s. Several French chefs began to offer foods that combined traditional French food with Asian cuisine, especially foods from Vietnam and China. The concept quickly spread to other major European cities, along with the American coasts.

Today, some of the most widely practiced examples combine European and Asian foods. Thanks to the wildly divergent culinary characteristics of these two cultures, combining centuries of cooking traditions of both continents can sometimes result in astonishing dishes. Vietnamese spring rolls might be found on the menu of a French restaurant, while a wasabi reduction sauce might be used on a pot roast. In the hands of properly experienced culinary experts, these fusions can be wildly successful.

Another path for fusion that other cooks take is to focus on simply combining the culinary traditions of two or more Asian nations. This type of cuisine was most likely also inspired by natural occurrences, as people from different countries exchanged recipes and ideas. Pan-Asian fusion cuisine tends to be more forgiving and less difficult to pull off well, since many Asian countries share common threads in terms of culture, as well as ingredients and seasonings used in their culinary heritage.

However, as is the case with all things associated with innovation, change and progress, haters of fusion cuisine never condoned the idea of mixing foodstuffs, dubbing it “confusion cuisine”, and arguing that chefs must only rely on novelty to carry the food, rather than flavour, texture and presentation.

Good fusion cuisine combines ingredients and cooking techniques from several cultures in a way that pulls together well, creating a seamless and fresh dish. Confusion cuisine, on the other hand, throws ingredients together like confetti, and sometimes causes an inevitable clash. Cooks intent on pulling off a successful cuisine research their ingredients carefully and think about how flavour and textures will combine for the diners. While novelty is certainly commendable, restraint is also important.

The Ascension of Cultural Cuisine

A lot of tasty goodness within the contemporary dining scene—fine or otherwise—owes a substantial amount of its popularity to excellent cross-cultural pairing and multilateral experimentation of culinary elements. Leaning more towards a food reviewer’s stance rather than that of a food critic, we firmly believe that proper fusion cuisine has brought more good than harm.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with the Korean taco – nothing malicious about the combination of kimchi and hot sauce, nothing terribly iconoclastic about bulgogi wrapped in billowy tortillas. If anything, the Korean taco represents a creative moment in foodie culture, the blending of two seemingly disparate taste profiles into a surprisingly tasty – and palatably coherent – meal.

“It’s really hard to invent new dishes, and even harder to invent new techniques,” Rachel Laudan, food historian and author of Cuisine and Empire: Cooking in World History, explains. “Almost all foods are fusion dishes.” But there’s a difference between food we easily recognize as fusion and food with a blended past that remains hidden to the casual observer. Dishes often thought of as extremely nationalized, like ramen in Japan or curry in India, often really have origins in the fusion of cuisines that met during colonial expansion and migration.

“When cultures mix, fusion is inevitable,” adds Corinne Trang, author of Food Lovers Vietnamese: A Culinary Journey of Discovery. As the hold of imperialism started to fall in the 19th and 20th centuries, a unique idea of nationalism began to take its place. As fledgling provinces struggled to prove their national might on an international scale, countries often adopted a national dish much like they adopted a flag or national anthem. Generally, dishes that were adopted as representations of a country’s “national” culture truly represented an area’s culturally diverse history. Take some of these dishes below as examples of “signature” dishes whose origins exemplify the blending of cultures into a classic fusion dish.

– Bánh Mì:

A typical Vietnamese street food, the bánh mì (specifically, the bánh mì thit) combines crunchy, salty and spicy notes to the delight of sandwich lovers everywhere. This typical Vietnamese sandwich represents a prime example of fusion food. A traditional bánh mì is made up of meat (often pâté), pickled vegetables, chillies and cilantro, served on a baguette. From the pâté to the mayonnaise, the influence of French colonialism here is clear as day. Held together by the crucial French baguette, the typically Vietnamese sandwich speaks of Vietnam’s colonial past.

Regardless of the ancient fusionist origin of bánh mì, the dish holds a significant place in Vietnam’s culinary present. “As long as there is demand you’ll always have the product. Basic business practice demands it. Why would you take something off the market, if it sells well?” Trang asks, explaining why this vestige of colonialism enjoys such modern success. “Bánh mì is convenient and delicious. It’s their version of fast food.”

– Jamaican Patty:

One of the most popular Jamaican foods, the patty, is similar in idea to an empanada (a dish which also has cross-cultural origins in itself): pastry encases a meaty filling animated with herbs and spices indigenous to Jamaican cuisine. But the snack dubbed “essential to Jamaican life” isn’t entirely Jamaican; instead, it is a fusion product of colonialism and migration, combining the English turnover with East Indian spices, African heat (from cayenne pepper) and the Jamaican Scotch Bonnet pepper. While the patty might be giving the Chinese noodle a run for its money in terms of late-night street food, its complex culinary history is much less rough-and-tumble.

– Vindaloo:

Vindaloo curry is an omnipresent staple in any Indian restaurant’s repertoire, but what no Indian school teaches in history classes is that vindaloo is actually a blending of Portuguese and Goan cuisine. Goa, India’s smallest state, was under Portuguese rule for 450 years, during which time the European colonists influenced everything from architecture to cuisine, including the popular spicy stew known as vindalho (the dropped ‘h’ is merely an Anglicized spelling of the dish.) The name itself is a derivative of the Portuguese vinho (wine vinegar) and ahlo (garlic), two ingredients that give the curry its unique taste.

The dish is a replication of the traditional Portuguese stew Carne de Vinha d’Alhos, which was traditionally a water-based stew. In Goa, the Portuguese revamped their traditional dish to include the chillies of the region, and today, vindaloo is known as one of the spicier curry dishes available. And Laudan also point out that “curry, as we know it, also has largely British origins,” indicating that this trend is not singular to vindaloo.

– Ramen:

The fluorescent-orange, plump white or clear broth of ramen noodles is a distinctive element of the Japanese culinary scene. The real dish, however, remains one dish that claims roots in Japan’s imperialist history and their interaction with the then enemy, China. In the late 1800s and into the early 1900s, Japan won a series of power struggles with China, allowing the island nation to claim various Chinese territories as its own (including Taiwan and former Chinese holdings in Korea).

Apart from land, they also assimilated their traditional Chinese noodle—saltier, chewier and more yellow due to the technique of adding alkali to salty water during the cooking process—and created a dish known as Shina soba, literally “Chinese noodle.” The name for the dish gradually tempered with time (Shina is a particularly pejorative way to describe something as Chinese) and came to be known as ramen, but its imperial history remains.

– California roll:

The California roll is a classic example of “American sushi”, early fusion cuisine incorporating new ingredients into traditional Asian recipes. The actual origin of this item is fuzzy at best, because like so many other popular dishes, the California roll has evolved.

One survey of historic USA newspapers confirms California roll-type dishes first surfaced in Los Angeles sometime in the early 1970s. These items were referenced under several names, with rare actual descriptions of these early prototypes. Those that exist confirm they did not include avocado, crab or mayonnaise.

The Dirty Secret

Beyond the dining table and further in the kitchen, today’s top secret perk (for some that chose to keep it so) is fusion, even more so than illegal charcuterie, MSG or even paid-under-the-table labour.

Though the culinary blending of cultures is more popular than ever, some chefs won’t readily use the “Bright Lights, Big City” era buzzword to describe what they do. Instead, they’ll tiptoe around the term, calling their handiwork “mash-ups,” “globally inspired” or simply “contemporary”.

It’s easy to see why. By 2007, when international writer David Kamp published The Food Snob’s Dictionary, fusion “had come so far out of fashion, it didn’t warrant inclusion,” he said. “The term itself had been discredited by poor execution in the ’80s, [thanks to] desultory places who didn’t know what they wanted to be, grabbing for a buzzword.”

When used in a critical way, some believe the term “cheapens” what they do. It doesn’t express the “passion, love, conceptual thought and labour” that went into signature creations that borrowed liberally and creatively from foreign palate of ingredients and flavours in a respectful and informed way.

Wolfgang Puck was another early standard-bearer. In 1983, the Austrian chef opened Chinois on Main in Santa Monica, California, blending French techniques with flavour profiles he was discovering in Los Angeles’s Asian neighbourhoods. “I’m going to do Chinese food the way I want to do it,” the chef recalled, telling stunned investors at the time. It was a smashing success, and soon the term “Asian fusion” was being used by countless cut-rate copycats—the kind of place, as Kamp put it, “that does sushi, but they also do Thai.” Read more about the Wolfgang Puck fusion movement a few pages ahead.

Semantics aside, whether they like it or not, food fusion has added many priceless and positive qualities when handled with finesse and flair as the delicate practice demands. Regardless of the negativity, no one would raise a hand of protest against Waku Ghin’s (Singapore) insanely tantalizing marinated botan ebi with uni and Oscietra caviar, or speak against the divine dishes coming from the multitude of Amber’s (Hong Kong) global ingredients such as Tasmanian truffles, Brittany blue lobster or Normandy diver scallops presented with sublime classic French techniques.

Fusion Over the Centuries

As we noted earlier, it is virtually impossible to pinpoint the origin of fusion cuisine. However, we do know of several defining events that helped popularize it throughout the last century or so.

There was obviously a lot more going on that we might have missed or deliberately left out, but hopefully the following timeline of events from different places around the world affirms the point that fusion cuisine has been around globally for ages, and how we’re grateful that it will remain with us for some time yet. Our list begins by roughly pinpointing the arrival of Asian tastes in Western countries.

ASIAN INVASION ERA

1850: The first Cantonese restaurant opens in San Francisco. The name of the establishment was not found on record, as it was most likely a restaurant based out of someone’s house with a modest-sized staff.

1884: Nippon Rioriya became the very first Japanese restaurant in London. Founder Mr. Matsusawa brought Japanese chefs, chopsticks and the small dinner service, just like back home. The restaurant’s uniquely creative aromatic flavours were completely different from what Londoners were accustomed to in that day and age. Talking about creativity, the restaurant’s name roughly translates to “Japanese restaurant”.

1885: Louis Sherry’s Mikado took New York by storm. Overnight, all things Japanese were the height of fashion. Sherry was called upon to cater an exclusive post-theatre party at a private town house and created Mikado-themed cakes.

1959: Against all odds and her ill-advising friends back home, Lai-iad Chittivej established Chada Thai, the first known record of a Thai food and beverage establishment in the US, located in Denver.

1961: The oldest print reference of a Vietnamese restaurant talks of a place called Viet Nam. The place is located on 1245 Amsterdam Avenue and is described as “a small, poorly air-conditioned, unpretentious place with an interesting cuisine modestly priced”.

THE AGE OF WOLFGANG PUCK

1983: Wolfgang Puck opens Chinois on Main in Santa Monica, California, providing a pioneering taste of Asian fusion and fried wonton-topped chicken salad.

1987: Nobuyuki “Nobu” Matsuhisa opens his first Peruvian-Japanese restaurant in Beverly Hills, unleashing a seemingly limitless appetite for miso-marinated black cod.

1989: Florida chef Norman Van Aken secures a place for “fusion cuisine” in the culinary lexicon in an address at a symposium on American cooking.

1992: The Cheesecake Factory goes public, bringing chicken chipotle pasta and other American fusion fare to the mainstream; Jean-Georges Vongerichten opens Vong in Manhattan with a menu of French-Thai fusion fare like sautéed foie gras with caramelized mango and ginger sauce.

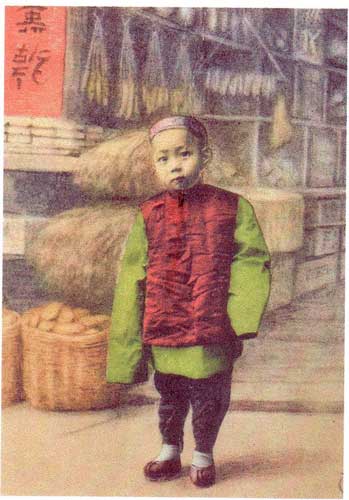

1994: In the Fusion Food Cook-Book, author Hugh Carpenter urges readers to pair spicy south-western fried chicken with ginger-apricot sauce, and watermelon salad with raspberry Cabernet vinaigrette.

CONTEMPORARY FUSION ERA

2001: Albert Sonnenfeld, co-author of Food: A Culinary History, says that fusion often combines too many things, confuses ingredients with flavour.

2009: Five years after opening the first Momofuku restaurant, Chef David Chang says he made peace with the term fusion via a last-minute bowl of grits with butter and soy sauce. Vong closes after 17 years.

2010: In an interview, Chef Danny Bowien reassures San Franciscans that his restaurant Mission Chinese will “not be some weird Mexican-Chinese fusion taco truck.” Instead he terms it “Americanized Oriental food”.

2013: Bowien opens Manhattan’s Mission Cantina. The menu includes dishes that might be described as Mexican-Chinese fusion—though not by him.

Present Day: Fusion cuisine continues to be a catchy global trend among restaurateurs and discerning diners.